Of all the wars of comparable length and severity in the past European conflicts, the damage to British commerce in Napoleonic wars stands out. Since the direct trading routes to the Baltic were blocked, on account of Napoleon’s Continental System, British trade to Northern Europe came to a standstill. However, the trade was resumed in 1814, only to be shut down again in 1822. The Russians probably realized their extent of likeness to the beer, and instead the Government decided to bring the prosperous business to their home country. On top of it, on and off high duties were placed on British stocks, including the Burton beer, and it made no economic sense to keep up with the trade anymore.

With the consequent stagnation in Baltic trades, several of the small-time brewers closed down the workings, while only the major five breweries (those of Allsopp, Bass, Worthington, Salt, and Sherratt) were able to pull through the next fifteen years. Although the opening of the Trent & Messer canal, precisely sixty-five years after the Trent Navigation, proved essential for the national customers in London, Manchester, Birmingham, and Liverpool, it was not until late 1822 that Burton’s true potential transcended everyone’s expectations.

Burton’s ultimate economic development

Mark Hodgson was a London brewer and the man behind the creation of India Pale ale. By the looks of it, he was selling a decent amount of his ale downstream to the Subcontinent market for a long time without a rival. Captain Chapman of India Service approached Allsopp with the suggestion to recreate the beverage. The idea was to boost the ale with more alcohol and hop so that it could better survive the long sea sails. This way, the drink would also be better suited for the warmer climate, rather than the usual fermentation for colder Baltic regions.

There came a time when Allsopp’s vigor brought out the best in his pale ale and became the article of standard among the commanders and officers of Indiamen who, pertinent to mention, were previously the largest investors of Hodgson. In mere four short seasons, Allsopp’s pale ale found a solid-home in Indian Community against all the oppositions by the company that had monopolized the market for nearly half a century. From this immense development by one brewer, the entire brewing industry of Burton was reaping the rewards of it in no time.

By 1832, Bass & Ratcliffe and Salt soon followed the exemplary Allsopp and Sons’ lead of venturing into the East India trade. Statistics show that ten years into the business and Bass was soaring with 43% of the annual 12,000-barrel trade to India while Allsopp’s earnings reduced to just 12%. Even more joyous were the years of the 1830s and 1840s, when Burton’s India Pale ale acquired a firm footing in the demanding local markets of London and Liverpool for the first time. As mentioned, the canal provided a cheap transport of casks, but the fact that Burton brewers acknowledged the power of railways early in their businesses that the productions flourished even further.

The opening of the Derby & Birmingham Junction railway in 1939 gave way to the unprecedented expansion of Burton’s brewing commerce. The remarkable growth rate was mostly accomplished by Bass and Allsopp, accounting for 60% of the total output of beer. By 1888, around 31 breweries in Burton produced close to three-millions barrels a year with over 8000 workers in their employment. One of the most astounding periods in Burton’s smart brewing history was the time when Bass & Co’s productions railroaded from a meager 11,600 barrels in 1831 to 538,000 barrels in 1868.

It would not be erroneous to say that this town that had faced misery upon misery in its past years of existence, now became the undisputed capital of brewers from all over the country. Between the town’s industry trebling in size with each passing decade and the incoming of brewing companies from London and elsewhere – notably Charrington (1872), Truman (1873), and Mann, Crossman and Paulin (1874) –the population of the town also mushroomed linearly. With most of the breweries seeking premises within the cramped boundaries of High Street and Horninglow street, the Victorian Burton saw a conspicuous change as tall, narrow chimneys now dominated its skyline.

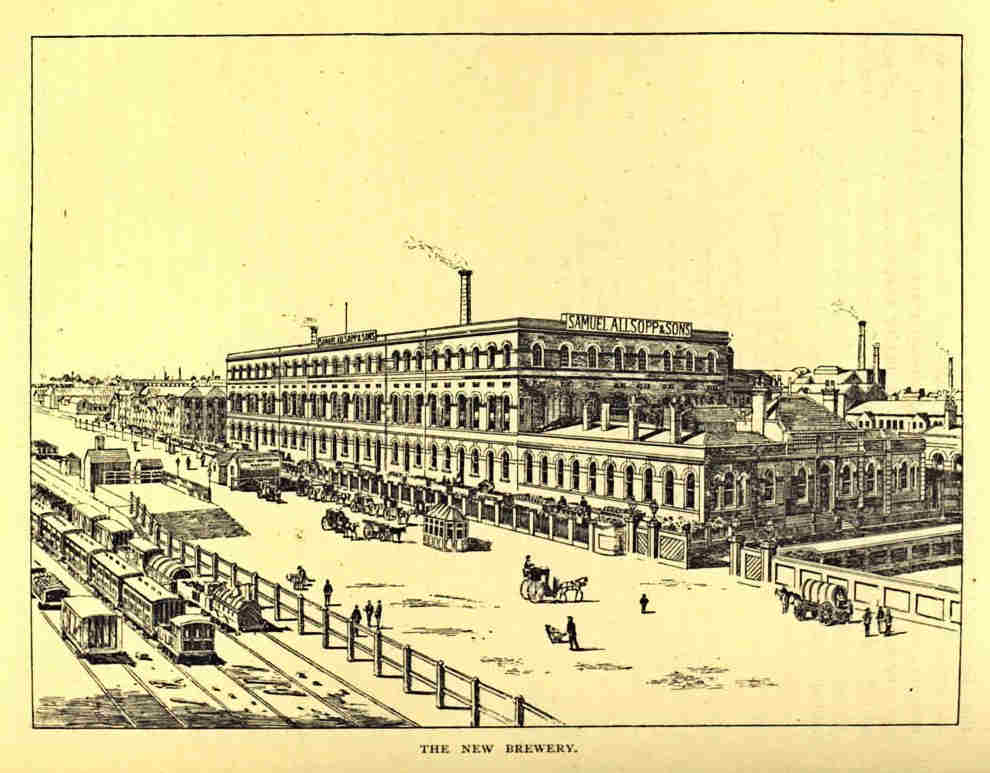

Allsopp had contracted London architects, Hunt & Stephenson, to fashion their 20 acres New Brewery (1859-60) alongside the railway tracks, under the supervision of an engineer, Robert Davison. By contrast, the old Bass brewery at New Street underwent multiple expansions with two more red-bricked breweries securing plots in Station Street in 1853 and 1863 (rebuilt in 1866 and 1884, respectively). Bass had multiple large maltings constructed, in particular, Bass Wetmore Malting (1862-64) to the north of Horninglow Street along the Anderstaff lane, and malting complexes at Shobnall (1871-79) with seven interrelated, slate roof ranges and one engine house, close to the Allsopp’s maltings. Most of the Bass buildings were strikingly consistent in designs and seems to be the work of a local architect Robert Grace with brewer engineers William Canning and later his successor, Herbert Couchman.

The construction of the Midland Railway in 1860 rescued the Parish from logistical problems with its branch railways and level crossings interlinking the malthouses with their associated breweries. Initially, only two branches were built after the Parliament’s consent: Guild Street Branch (1861-62) and Hay Branch (1861-65). Soon enough, a grid of private lines started to appear, and a survey from 1869 shows Allsopp, Bass, Ind Coope & Co, and Worthington, each operating their railway sidings. By 1878, Burton-on-Trent’s railway system had spread out to at least an area of four-square miles, of which Bass was controlling the 17 miles track with its 11 steam locomotives, no doubt designed by Burton’s famous engineers, Thornewill & Warham.

The brewers at Burton were probably the first of many global brewers to hire efficient chemists to conduct necessary researches into the raw materials and to reevaluate the practicality of their brewing process. Among the first of these were John Mathews at Bass and Henry Bottinger at Allsopp in 1845. After them, Cornelius O’Sullivan, Peter Griess, Horace, and Adrian Brown, almost all qualified by the Royal College of Chemistry, were later employed by the Burton brewers. Their contributions not only made brewing continuous – all year round – but also reined in more profits from international markets.